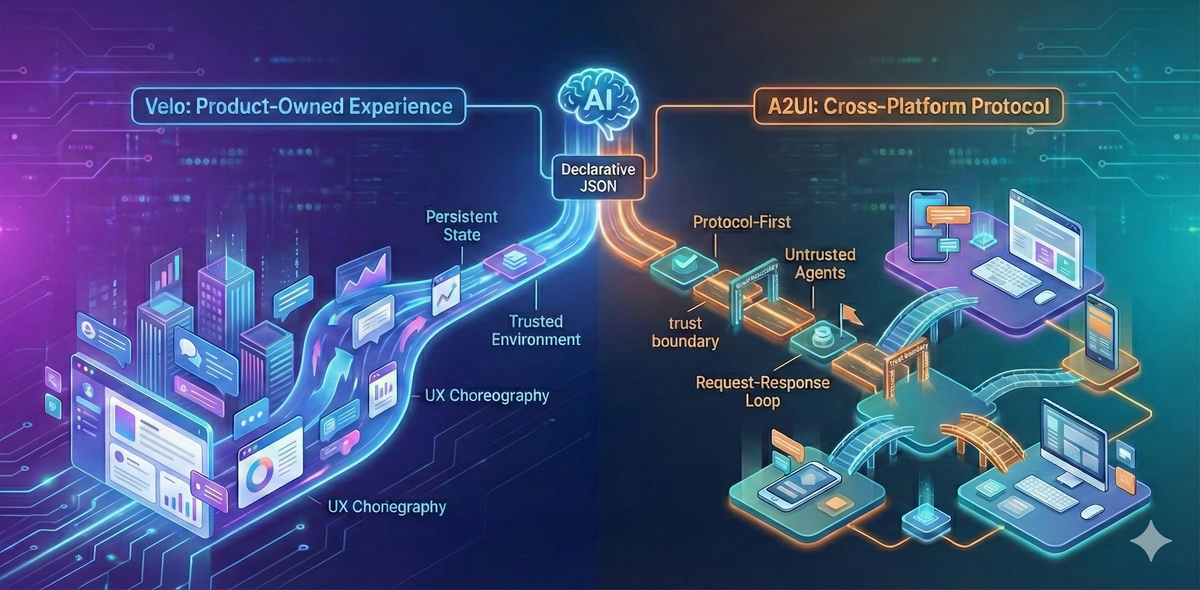

Velo and A2UI: Two Paths to Agent-Driven UI

Context

Google's recently open-sourced A2UI, a protocol that lets AI agents generate declarative UI (as JSON) rendered by host applications using native components. The goal is to let agents “speak UI” safely across platforms and trust boundaries.

Teams building product-owned agent experiences are starting to ask how A2UI compares to systems like Velo - how do their current capabilities stack up and where does each approach make the most sense?

High-level takeaway

Before comparing, it’s worth calling out one key assumption up front. A2UI is explicitly designed for environments where the UI-generating agent is remote and potentially untrusted. Velo does not have that constraint. We control the agent, backend, and client, which gives us the freedom to be more opinionated about experience, pacing, and design-system constraints. That difference heavily shapes the tradeoffs each system makes.

A2UI is validating, and it solves a class of problems adjacent to ours, but it doesn’t materially change the direction Velo is already taking.

At a high level, both systems are solving the same problem: agent-driven, declarative UI rendered on the client. The difference isn’t in the idea itself, but in the tradeoffs each system is designed to make.

A2UI is protocol-first and optimized for cross-organization, untrusted agents. Velo is experience-first and optimized for continuity, pacing, and real product constraints.

In short, A2UI reflects the tradeoffs you make when interoperability and safety are the primary concerns, while Velo reflects the tradeoffs you make when optimizing for user experience within a single product.

1. Design systems are more than “styling”

A2UI says that “the client owns styling,” which is technically true, but incomplete.

In practice, design systems encode real constraints, such as:

- Design tokens

- Spacing and layout rules

- Accessibility semantics

- Responsive behavior

- Motion and animation principles

These are not cosmetic choices. They define what UI can and cannot render.

In Velo, these constraints are baked directly into the component primitives the agent can use through our shared component UI Library. The agent isn’t styling things. It’s composing from primitives that already behave correctly.

A2UI assumes each client will enforce these constraints correctly on their own. That can work, but at scale it’s optimistic and easy to get wrong.

2. UI as output vs UI as a stateful narrative

A2UI largely models UI as something that the agent outputs and updates over time. This isn’t about replacing chat, but about using a richer UI when text alone stops being the best way to move the user forward.

Velo treats UI as part of the conversation itself:

- Components persist and evolve over time

- Not everything is replaced on each turn

- New UI references earlier context

In A2UI-style flows, replacement is common. In Velo, persistence is the default and replacement is the exception.

This makes the interface feel more like a living transcript than a series of responses, reducing the need for users to mentally reconstruct context.

3. UX choreography is a first-class concern

A2UI focuses on what to render, not how it unfolds.

Velo explicitly owns UX choreography, including:

- Animation sequencing

- Scroll anchoring

- Progressive disclosure

- Restore-without-reanimate behavior

These details shape how the assistant feels and how users understand change over time. Velo owns the client, so it can make opinionated UX decisions centrally instead of pushing that responsibility onto each implementation. This is where the agent owns the intent while the client owns the experience, allowing the UI to remain coherent even as it becomes more dynamic.

Comparison table

| Dimension | A2UI | Velo |

|---|---|---|

| Primary goal | Cross-agent, cross-organization UI protocol | Product-driven conversational UI |

| Trust model | Untrusted / remote agents | Fully owned system |

| UI definition | Declarative JSON protocol | Declarative render instructions (JSON-based) |

| Design system | Client-owned, loosely defined | Enforced via shared component library |

| Accessibility | Client responsibility | Built into component primitives |

| Motion & pacing | Out of scope | First-class concern |

| UI lifecycle | Request → response → update | Stateful, evolving transcript |

| Scope | Generic, framework-agnostic | Opinionated, product-specific |

An area worth exploring further

One place where A2UI is ahead of Velo is in examples where agents introduce custom, task-specific UI in response to open-ended questions.

For example, a user might ask:

“Show my sales breakdown by product category for Q3”

And the agent responds with both:

- A textual summary

- A purpose-built visualization, such as a chart

In many product-owned agent systems today, richer visualization-style components tend to appear in known flows rather than fully open-ended queries. This is an area where the underlying declarative model makes future expansion possible.

That said, the underlying declarative structure already supports this direction, making it possible to grow beyond strictly chat-shaped interactions and into richer, mixed-mode conversational experiences.

Velo vs A2UI: UI lifecycle diagrams

A2UI mental model

A2UI follows a request → response → update loop. Each agent turn produces a UI that may replace or update the previous UI.

User input

↓

Agent decides

↓

A2UI JSON payload

↓

Client renders / updates UI

↓

(wait for next user input)This model works well for stateless or lightly stateful interactions, especially when agents are remote or untrusted. The UI primarily reflects the agent’s latest response.

Velo mental model

Velo treats UI as an evolving conversation surface. New instructions add to, modify, or reference existing UI instead of replacing it wholesale.

Conversation starts

↓

Declarative render instructions (group A)

↓

Declarative render instructions (group B - references A)

↓

Persistent components stay anchored

↓

New components animate in

↓

Conversation continuesHere, the UI itself carries memory. Some elements persist, some evolve, and others are intentionally transient. Users can track progress visually without mentally reconstructing context.

Velo feels less jumpy and better supports longer, multi-step interactions. This also gives us flexibility to grow beyond a strictly linear chat UI and introduce non-chat components like charts, overlays, or persistent sections without breaking the existing model.

What Velo is intentionally not solving

Velo is not designed to be a cross-organization UI protocol. It does not optimize for untrusted agents, universal portability, or framework neutrality. Those are valid problems, but they are not the problems Velo is trying to solve today. This focus allows Velo to be more opinionated about experience and correctness, rather than generic by necessity.

Conclusion

A2UI demonstrates how declarative UI can work across untrusted, cross-platform environments. Velo takes the same foundation and pushes it deeper into experience, choreography, and long-running interaction design. Seen together, they reflect a broader industry shift toward agents that don’t just generate text, but participate directly in shaping user interfaces.