I built a custom text-to-sql agent for Snowflake and so can you!

I built a custom text-to-sql agent..

That’s a lie. I just told Cursor how to query tables and that’s good enough.

If you’ve used an agentic coding tool, you’ve seen how well agentic tools work with command line tools. With the right rules (or skills for Claude code, makes very little difference) plus some common sense guardrails, you can have Cursor write your SQL for you. No MCP required.

It needs a way to talk to the database, and a description of the tables it’s going to query.

Here’s what you need, specifically:

- A CLI tool for running SQL queries (

snow sqlfor Snowflake,psqlfor Postgres,duckdbfor DuckDB, … you get the picture). - A rule describing how to use the SQL CLI for your db.

- A folder of table descriptions, with sample queries for whatever you commonly query for.

- A rule describing how to look for table descriptions.

This will work very well for most software engineering and some data engineering type queries – if you regularly check tables in your warehouse to answer questions with SQL (“How many threads have more than four messages?”), you can use these tools to automate a lot of that work.

Note: this configuration is for developer tools, not business users. Business users require a little more detailed data descriptions, specifically a “semantic layer” that maps business metric definitions to tables and queries. That’s a more complicated setup than I’m showing here.

Database CLI

As an example, I’ll use snow CLI, but as mentioned this can be any command line interface to a database that you are using. I’ve personally gotten this working for Snowflake, Postgres, DuckDB, and BigQuery – all without any MCP setup.

For any of them the most important things are:

- queries without browser auth every time (once per session is fine-ish, once per query is too slow) and

- a read-only role to run the queries with.

For Snowflake, I used their config.toml format with an RSA key and a passphrase in the environment, and connect with a read only role. For Postgres, I use pgservices / pgpass, again with a read only connection. DuckDB has the --read-only flag and is just a file, so it’s the simplest.

Having quick hands-off authentication and a read-only role is critical because the agent will make multiple queries when trying to answer your question, just like a human would. You don’t want to have to click a button every time it makes one, but you don’t want it truncating your warehouse either. Having both set up allows the agent to safely do what it needs to do.

Rule describing your CLI

For Snowflake, I noticed it continually burned a tool call on snow sql --help, so I dropped that into a rule along with guidance for the LLM about authentication (mainly, it doesn’t have to worry about it).

---

description: Querying snowflake for schema or data.

alwaysApply: false

---

Use `snow sql` to execute queries against Snowflake.

There is no need to include any connection information, that is already configured, it will just work.

This is the help entry for `snow sql`:

Usage: snow sql [OPTIONS]

Executes Snowflake query.

Use either query, filename or input option.

Query to execute can be specified using query option, filename option (all queries from file will be executed) or via stdin by piping output from other command. For example cat my.sql | snow sql -i.

... # the rest of the help text.The main purpose of this rule (and the others) is to save context by removing repetitive tool calls and thinking. The LLM gets it right eventually, but this rule/skill helps it get things right faster and cheaper.

For Postgres, I found the LLMs usually got commands right the first time without the help guidance, probably because psql has been around a lot longer. You will still want a rule for it so you can describe which connection services are available, and when to use each one.

---

description: Querying Postgresql to test SQL or verify data.

alwaysApply: false

---

When calling postgres, use

```

psql service=mydatabase -X -qAt -c '<YOUR QUERY>'

```

pg service conf and pg pass are set up for the user.

You do not need to explicitly pass credentials to `psql`.

### Available services

* mydatabase - database that is mine, used for me stuff.

* ... other services if you need them.Folder of table descriptions

Once you have the rules on how to query, you can technically get started. But you’ll notice pretty quickly that the LLM tends to repeat the same queries … `DESCRIBE TABLE` / \dt / SELECT * LIMIT 5 … the stuff that tends to appear at the top of every Jupyter notebook or Snowflake worksheet anyone’s ever written. This is unnecessary overhead. Most of the time that information doesn’t change, which presents an opportunity to pre-compute it.

The idea behind this is similar to a rule, but is specific to tables you need queried. Again, we’re not doing anything the LLM couldn’t do itself, we are making it more efficient by pre-computing a lot of the context we know it will need.

I use a standard naming scheme, {table_name}_table_description.md. The more uniform and predictable you can structure your descriptions, the better the agent gets at using it.

Here’s what the file looks like for a fictitious table that stores chatbot interactions, as an example.

**Table:** `public.chatbot_messages`

## Overview

This table stores example chatbot interactions for demonstration and educational purposes.

Each record represents a single request/response exchange, capturing the input text sent to a chatbot and the text returned in response. .

## Schema

| Column Name | Data Type | Nullable | Primary Key | Description |

|------------|-----------|----------|-------------|-------------|

| `id` | UUID | No | Yes | Unique identifier for the message record |

| `conversation_uuid` | UUID | Yes | No | Identifier used to group messages into a single conversation |

| `input_text` | TEXT | No | No | The full text sent to the chatbot |

| `output_text` | TEXT | Yes | No | The full text returned by the chatbot |

| `created_at` | TIMESTAMP | No | No | Timestamp when the message was created |

## Key Use Cases for Analysis

### 1. Conversation Review

Group messages by `conversation_uuid` to reconstruct multi-turn conversations.

### 2. Input/Output Comparison

Compare `input_text` and `output_text` to evaluate response quality or behavior.

### 3. Volume and Timing Analysis

Analyze message volume and trends over time using `created_at`.

## Sample Query

```sql

SELECT

conversation_uuid,

input_text,

output_text,

created_at

FROM public.chatbot_messages

ORDER BY created_at DESC

LIMIT 10;Obviously, I didn’t write that file. But I did have the rule for database queries set up, and I did guide the LLM a bit. Telling it “describe this table” is better than nothing, but if you tell it the most important things you do regularly, it will pre-build those queries in the file and will have a much higher success rate when you ask it something almost-but-not-quite-the-same in a later session.

SQL is very general, and an analytics engineer checking out trends is going to use different queries than a dev looking for bad records. So tell the agent what you’re going to do with each table. That effort is time well spent: once I started using these rules, I found that the LLM can run successful queries in one shot without any auxiliary queries for schemas or sample data.

Rule describing how to look for table descriptions

Since table descriptions aren’t rules themselves (maybe they could be, I haven’t tried it), the agent will need to know where / how to look for them. You can add a rule/skill describing where the descriptions are and when to read them. That rule should have your naming convention. Here’s the Cursor version; a Claude Code skill will look basically the same (slightly different front matter).

---

description: Use this rule to before querying tables in Snowflake, to gather context about any tables we have context for.

alwaysApply: false

---

# Overview

The `snowflake_tables` directory contains markdown descriptions of specific Snowflake tables, including sample queries for common operations. Each file represents one table, and is named `{table_name}_table_description.md`.

When asked to query a table in Snowflake, check this directory for a corresponding table description and _read that file_. By doing this, you will save a lot of time making boilerplate queries to determine table structure and common patterns.

These files are designed to **save you time**.If you find the agent making multiple queries to a particular table, or queries start failing, re-build this file. You could try adding a section telling the agent to let you know if it sees a change, too. I haven’t had the opportunity to test it yet but it seems like that would work, with some tuning.

All Together

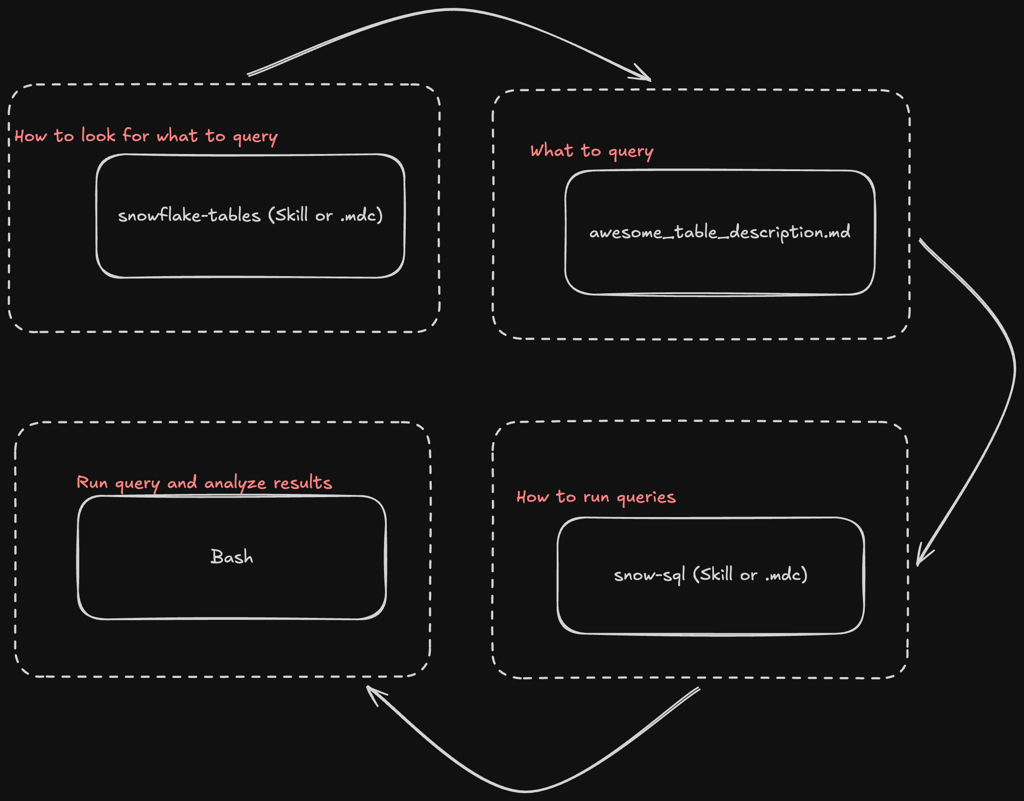

Here’s the flow of context from user input to agent query. In practice, some of this is done in parallel (usually the snowflake-tables / postgres-tables / whatever-tables rule and the snow-sql / psql / … rules), but this is the general idea.

First it uses the tables rule to find the table descriptions. Next, it reads the table description based on the file name. After that, it reads the rule on how to run queries, then finally it runs the query. It will usually repeat this a few times until it can gather enough data to answer the question, since most meaningful questions require a couple of queries and some iterations to answer.

Conclusion

I’ve been using this setup since early December, and it has saved me a ton of time. I no longer even open Snowflake itself to run queries and solve problems with data. I open Cursor. For Claude Code, you can turn the cursor rules into skills. It’s all just markdown anyway.

Examples of things I’ve analyzed with this:

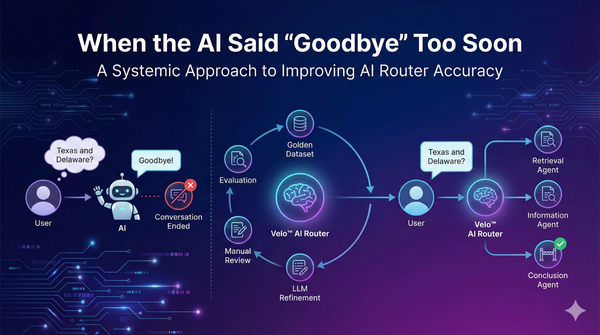

- Why has the token usage for Velo™’s retrieval prompt gone up in the last three weeks?

- Build me an evaluation dataset for aligning an LLM judge to Velo™’s retrieval agent. Focus on recent conversations about taxes, but include others for variety.

- Has the number of search results with no documents retrieved gone up recently?

In all cases, this setup has saved a lot of time and tokens, allowing both me and the LLM to focus on the real questions instead of constantly chasing SQL syntax and table descriptions.