Breaking Bottlenecks, Not Teams: Applying the Theory of Constraints to Software Development

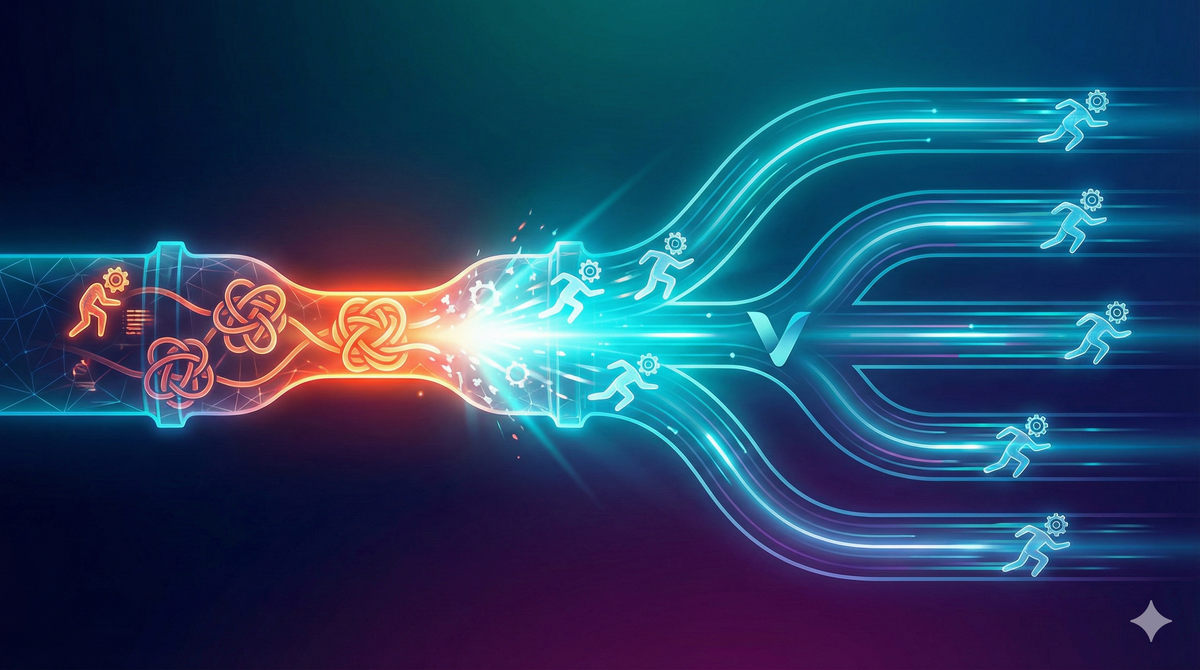

The Theory of Constraints (TOC) teaches a simple truth: every system has a limiting factor that determines its overall performance. Improving anything other than that constraint is wasted effort. In manufacturing, that constraint might be a slow machine. In software, it is often the people who carry the highest cognitive and contextual load.

TOC was introduced by Eliyahu Goldratt in the 1980s through his book The Goal. It originated in manufacturing as a way to identify and manage the single most limiting factor that determines a system’s overall performance. Rather than trying to optimize every part of a process, TOC focuses improvement efforts on the true bottleneck, ensuring that each change increases total throughput. This focus on continuous improvement, waste reduction, and flow became a cornerstone of modern lean principles and is now applied across multiple industries to drive efficiency and clarity of purpose.

When we set out to build Velo™, we knew that speed would come from focus, not force. Adding people, process, or tools to solve every problem would only make the real bottleneck worse. The Theory of Constraints became an important mental model for how we developed the product and how we organize the work behind it. Keeping that mindset has only accelerated feature development and product maturation since launch.

The Real Constraint in Software: Cognitive Load

The biggest constraint in any software team is not code, infrastructure, or funding. It is focus. The development team’s time and attention are finite. Every additional request, tool, or report divides that focus.

Product managers, analysts, and management have legitimate needs during the product development, but traditional approaches add overhead and cost. It often starts with good intentions. Someone asks for a new dashboard to track performance or a report to summarize system health. Each request feels reasonable in isolation. But over time, these requests compound. The development team becomes responsible not only for building the product but also for building and maintaining the systems that describe how it is being built.

That kind of overhead looks like progress on paper but erodes throughput in practice. The constraint (the developers) spend more time maintaining visibility than creating value. And, lets face it...every report or dashboard has a half-life and its usefulness begins to wane the moment its published.

Protecting the Constraint

The goal is not to share the burden of the constraint across more people. It is to protect it. Adding people always adds overhead.

We decided early on that our engineers should not be building tools just to manage the tools. Instead of spinning up new frameworks or analytics services every time we needed insight, we adopted a just-in-time approach to tooling. We build only what is necessary, only when it is necessary.

When the product or program teams need data visibility, they built it themselves using lightweight frameworks like Snowflake Streamlit to build temporary dashboards on top of production data. These are often simple, purpose-built apps that serve a single use case and are discarded once they have served their purpose. All it takes is a basic understanding of python, knowledge of the data structure, and an AI assistant.

If a team needs quick insight into behavior or adoption, they can generate queries or data visualizations using AI tools like ChatGPT or Gemini. This allows non-engineers to pull meaningful information without waiting for developers to build or maintain another reporting layer. Need to trouble shoot prompt outputs, you don't need to learn the heavy-weight evaluations tools when a simple viewer app will suffice.

By keeping tools simple, ephemeral, and built at the point of need, we reduce long-term complexity. Developers stay focused on building Velo™. Everyone else gains the autonomy to explore, learn, and contribute without creating new dependencies.

Building Tools Only When You Need Them

The idea of just-in-time tooling applies not only to analytics but to every layer of the development process.

If a new requirement emerges, we first validate that it addresses a real constraint. If it does, we solve it as directly as possible. If it does not, we park it until it becomes one. Building features that no one uses is also a waste of your constrained resources.

Thinking like this keeps the system lean. Instead of accumulating dashboards, internal APIs, or half-finished frameworks, we create short-lived, targeted solutions that solve specific problems. Streamlit, for example, gives us a way to turn a Snowflake query into a functional tool in minutes, not weeks. AI tools can automate much of the scripting and scaffolding required to get there.

This approach encourages experimentation without committing the engineering team to long-term maintenance work. We use AI and modern tooling to turn ideas into insights quickly, so we can make decisions based on real data instead of assumptions.

Expanding the Constraint with AI

Artificial intelligence tools like have become an integral part of how we work. They allow product and program team members to contribute directly to development tasks that once required engineering time.

Need a quick SQL query to test a hypothesis? ChatGPT can write it. Need to refactor a Streamlit app to display new metrics? Cursor can handle the boilerplate. These capabilities mean that product managers and analysts no longer have to depend entirely on engineering bandwidth to move forward.

AI does not replace developers. It expands their capacity by removing the need to perform repetitive or low-leverage work. It allows the constraint to focus on high-impact architecture and design decisions while others handle exploration and iteration.

The Paradox of Productivity

When teams hit a slowdown, the instinct is to add more people, process, or structure. In TOC, that often makes things worse. Adding effort to a constrained system increases coordination costs faster than it increases output.

Software projects rarely fail because teams lack talent or dedication. They fail because effort is misplaced. Every meeting, every new status report, every new internal tool, every additional process step adds weight to a system that is already struggling to move.

The better question to ask is whether a new idea or initiative will reduce friction or add it. If it adds friction, it waits. If it removes friction, it proceeds immediately. That discipline is what keeps development velocity real instead of performative.

Building for Flow, Not Force

Building Velo™ has reinforced the lesson that true velocity is not about more resources. It is about removing friction and focusing effort on what matters most.

We have learned that protecting the constraint means empowering everyone else to contribute intelligently. It means using Snowflake Streamlit to create data visibility without new infrastructure. It means using AI tools to accelerate iteration without expanding the backlog. And it means letting go of the idea that every internal problem needs a permanent system-level solution.

The Theory of Constraints is not just a principle of manufacturing. It is a framework for creative focus. When applied to software, it keeps teams honest about what really limits their progress and helps them design systems that move at the speed of learning, not the speed of process.

Conclusion

Velo™ was built around principles that prioritize clarity, simplicity, and velocity. Those same principles guide how we build and scale the tools that support it.

By recognizing that the constraint in software development is focus, not effort, we have designed our process around protecting and expanding that focus. Leveraging modern tools and AI has allowed every member of the team to contribute where they add the most value without overloading the system.

The result is a product that evolves faster, with less waste and more purpose. That is what it means to apply the Theory of Constraints to software development, and it is the reason Velo™ continues to grow stronger and faster with every iteration.